The differences in emissions’ accounting matter to reach the goals in the Paris Agreement

August 02, 2024

The Paris Agreement of 2015 set the goal of limiting global warming to 2°C, and preferably to 1.5°C, compared to pre-industrial levels. To achieve this and avoid a potentially catastrophic scenario for the planet, there is a critical need to drastically reduce global anthropogenic greenhouse gas emissions (GHGs) in the short term and reach net-zero emissions by the second half of this century (by 2050 for the 1.5°C target or by 2070 for the 2°C target).

The first global stocktake of the Paris Agreement, whose results were revealed at COP28, yielded discouraging conclusions. According to this assessment, achieving the agreed-upon goals requires a 43% reduction in emissions by 2030 compared to 2019 levels. However, countries' commitments, as expressed in their Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs), only aim for a modest 2% reduction in emissions by 2030 (or 5.3% if conditional commitments are included). This highlights the necessity for a more ambitious collective effort.

There is an additional complexity concerning emissions reductions proposed by countries related to land use activities (e.g., reducing deforestation or increasing reforestation). The complication arises because countries use a criterion to account for these emissions and absorptions (and to set their national targets), which differs from the criterion used by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) for climate projections and determining global emission pathways required to meet specific global warming targets.

The complexity of measuring emissions from Land Use and why it matters

The complexity of measuring emissions from Land Use, Land-Use Change, and Forestry (LULUCF) stems from simultaneous anthropogenic and natural carbon emissions and absorptions that are difficult to separate. For instance, reforestation increases in carbon absorption due to land-use change is considered anthropogenic, while natural growth of forests due to increased atmospheric CO2 enhances carbon absorption is considered natural.

There are two globally accepted approaches for accounting these flows. IPCC estimates of global emissions consider only anthropogenic flows within the LULUCF sector, while natural flows are part of the land’s role as a natural carbon sink. This separation is based on models estimating vegetation growth due to increased CO2 in the atmosphere and their associated flows.

Conversely, countries account for LULUCF emissions in their national inventories under the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) guidelines. These guidelines simplify LULUCF’s emissions accounting by including all flows on lands declared "managed," without distinguishing between anthropogenic and natural flows.

LULUCF’s emissions in national inventories tend to be lower than those reflected in accounting models. This is due to increased absorption by forests and other natural carbon sinks as a result of higher emissions – absorption rises due to increased CO2 in the atmosphere-, and these absorptions are included in national LULUCF inventories but not in accounting models. According to Gidden et al. (2023), the discrepancies between both sources are significant: between 4 and 7 gigatons of CO2 per year, which amounts to 10% of global GHG emissions.

These differences are critical for assessing progress towards Paris Agreement goals, as reduction targets refer only to anthropogenic flows. Because UNFCCC criteria tend to underestimate LULUCF emissions, progress towards emission reduction goals may be overestimated. If IPCC climate projections were based on national inventory criteria rather than global models, achieving the 1.5°C global warming target would require 3% to 6% greater emission reductions by 2030 and net-zero emissions would need to be achieved 1 to 5 years earlier (Gidden et al., 2023). In other words, progress towards the collective goal of limiting global warming is even less than it appears.

Latin America and the Caribbean’s emissions according to different criteria

The discrepancies between these two accounting models are particularly relevant in Latin America and the Caribbean, where the LULUCF sector is the primary source of GHG emissions, accounting for 38% in 2019. According to Grassi et al. (2023), LULUCF emissions in the region are 50% lower in national inventories compared to global carbon cycle models, a difference averaging 1 GtCO2 per year.

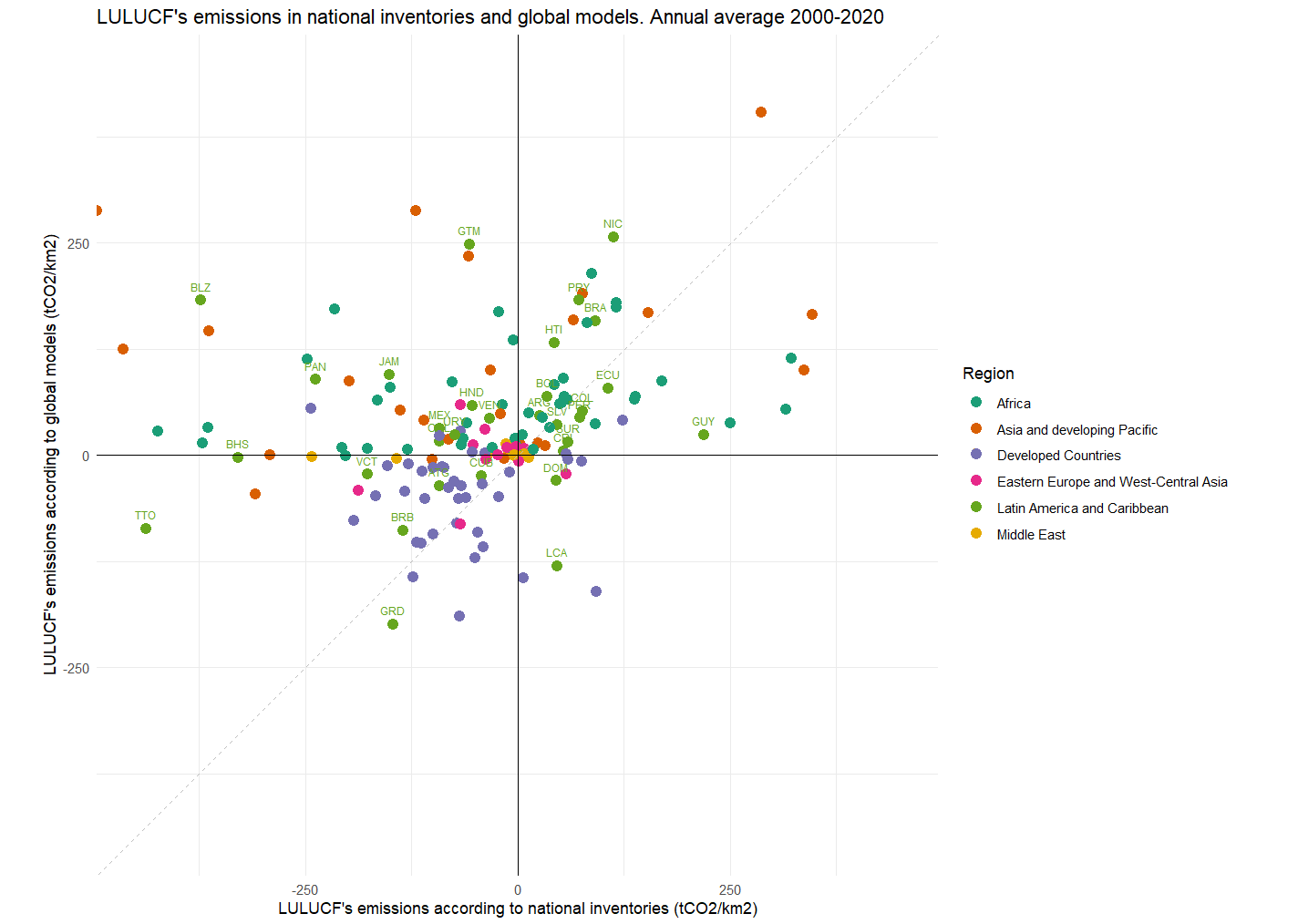

The graph shows the emissions from the LULUCF sector (annual average between 2000 and 2020) according to both criteria. According to global models, out of the 33 countries in Latin America and the Caribbean, 23 are net emitters in this sector and 10 are net sinks. However, according to national inventories, only 15 are net emitters and 18 are net sinks. Additionally, out of the 13 countries that are net emitters according to both criteria, in 6 of them, emissions according to national inventories are lower than those indicated by global models.

In conclusion, the criteria used to account for land use emissions are crucial for evaluating progress towards Paris Agreement goals. The outcomes of the first global stocktake underscore the urgent need to increase short-term climate ambition to keep these goals within reach. The additional effort required is even greater when considering the discrepancies in measuring LULUCF emissions criteria.

Florencia Buccari

Officer at the Socioeconomic Research Directorate of CAF

Pablo Brassiolo

Principal Economist, CAF -Development Bank of Latin America-